When Blesma Member Stanley Morgan was admitted to the Royal Surrey Hospital with severe Covid symptoms, lead Chaplain Adrian Teare spent time with him. This is his account of Stanley's story...

You can’t see it,” says Stanley, his eyes glistening with the heavy tears of a long life ebbing and flowing through each breath. “You can’t see it,” he says again, gripping my gloved hand, “but I’m travelling to Jill now!”

The clock has long since struck 8pm and the clapping has finished. The wards are hushed on Stanley’s last night in hospital, and his excitement can’t be contained. But it was not always this way. Some weeks earlier, the Senior Sister on duty in the Emergency Assessment Unit called through to Spiritual Care.

She described a lovely man who had come into EAU and who was very sick. He was one of the many coming in suffering from coronavirus, and was asking to see a priest. He was Roman Catholic Christian, but as the building was in lockdown no-one from outside could come in.

“I’ve explained it to him. He’s called Stanley, and he says he just wants to see someone,” said the Senior Sister. “Will you come?”

Gasping for air

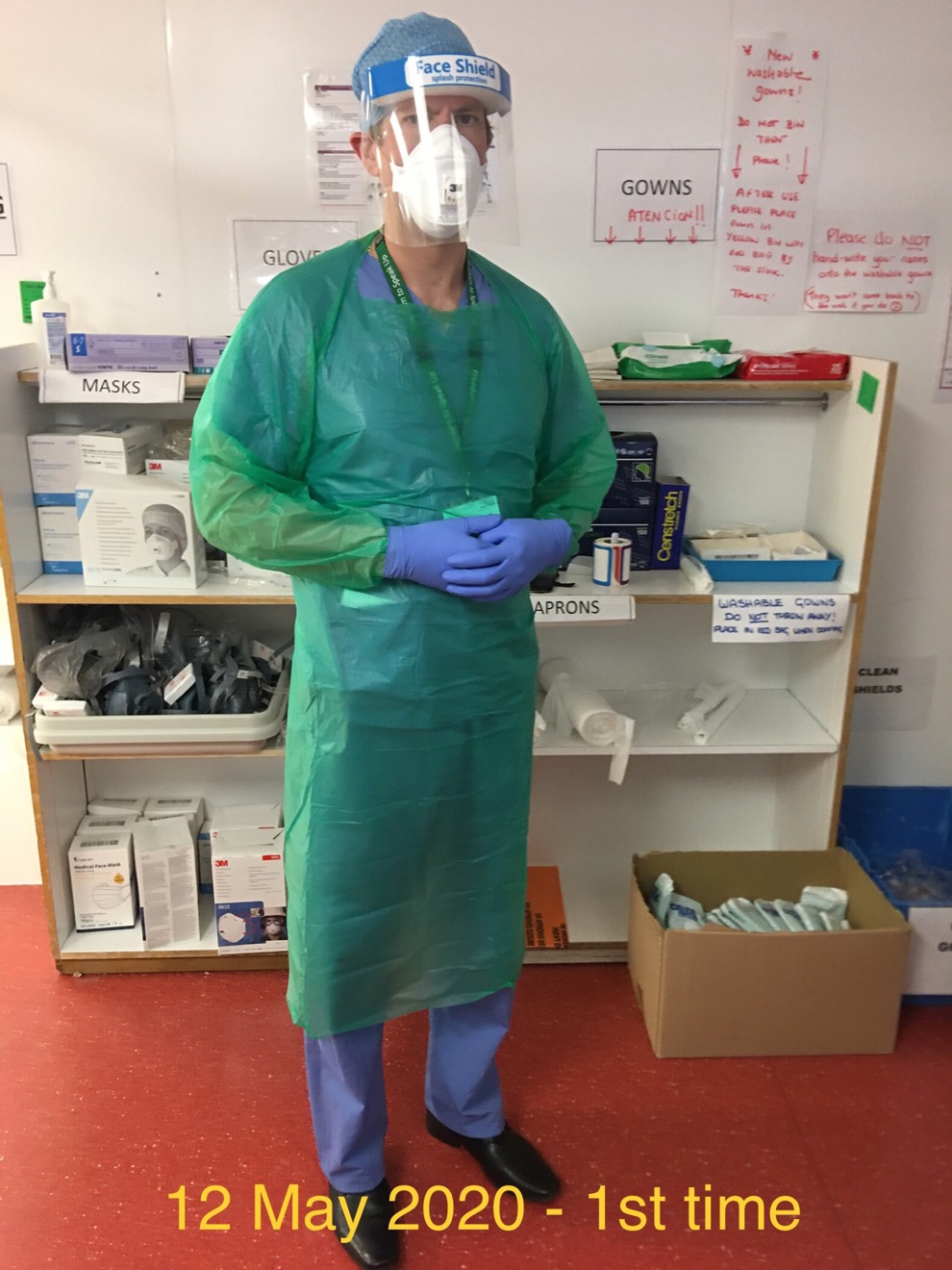

It is a nervous time when you don Personal Protective Equipment. It takes time and concentration to layer up: first the gloves, then the gown, then more gloves, goggles and a hair net, all crowned with a visor. A little wiggle to check that everything is in place and I laugh with the nurse helping me. I am sure I am not alone in asking myself if this is the time I catch it too.

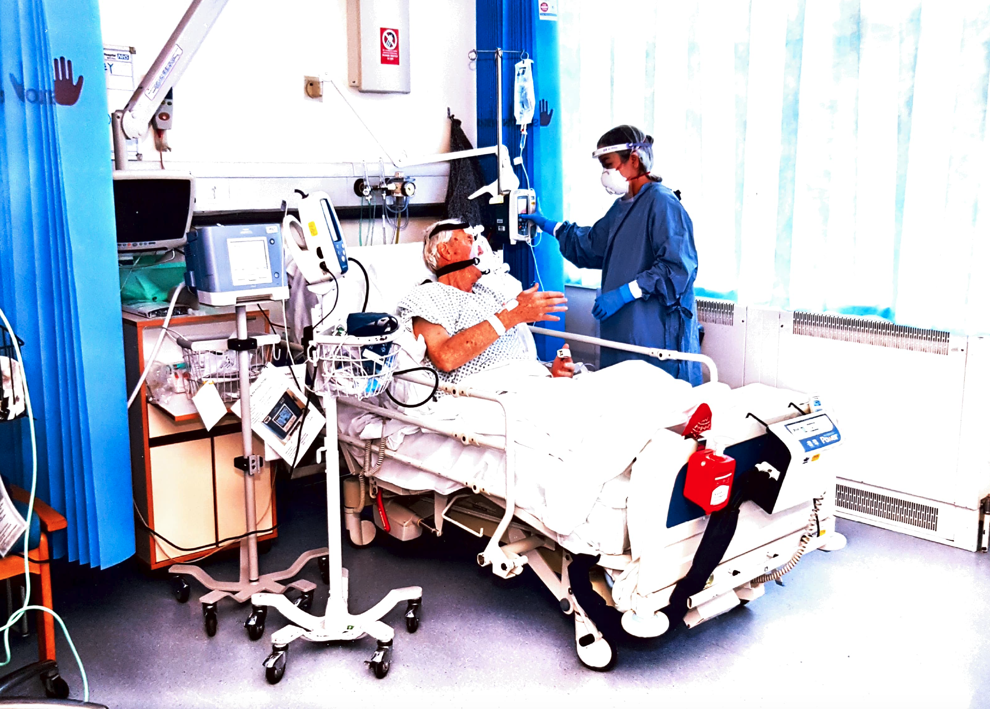

Stanley is in a C-Pap mask. He is gasping for air, wincing with the pain of breathing. Each breath is terrifying for him; full of pain and effort. This will continue for weeks. The month is April, the day is Tuesday, and the time is 1.00pm. As he breathes out, Stanley watches his chest lower, and then forces his lungs to re-inflate.

Walking into a COVID-19 ward is a disorientating experience. Already wrapped in layers, your goggles start to steam up and your visor is unclear. The standard visual metrics of height and breadth and length and depth are slowly disappearing as I walk towards the bed. The C-Pap mask completes the disassociation of space and time with the whistling noise of the air, and words spoken fight in the oxygen flow and float around each other inside the mask.

Stanley does not have access to the internet. He does not have a mobile phone. It doesn’t matter, however, because he does have something to say. He has a message for Jill, his wife of 59 years. At his bedside, I make my introduction and a first apology. “Hello Stanley!” I say as cheerily as I can, “my name is Adrian and I am the Lead Chaplain. Sorry I cannot get a Roman Catholic in to see you today, I’m Church of England.”

“That’s ok,” he pushes out. “I just want to see the Padre.” I ask Stanley whether he has been in the Armed Forces as he is asking for the Padre. “Yes I was,” he says, his excitement growing. He was a National Serviceman in days gone by. “I was in the Royal Artillery.”

The way that they have cared for me and my wife since I've lived in this part of the world...Thank you for saving my life"

“Well Stanley,” I reply, “that’s very interesting because I am a Padre to the Royal Artillery in my spare time. Tell me what it is that I can do for you.” Stanley tells me his phone number, and I scribble it down. Now I am able to pass a message to Jill. Then he tells me Pat’s number. Pat is his Blesma Support Officer and is like family (I quickly learn that all of Stanley’s friends are.) I have to leave his bedside as the desperate rasping draws air into his afflicted lungs.

I cannot risk hurting him by asking for more. He takes hold of my gloved hand and asks for some prayer time, and we pray for the doctors and nurses in the EAU, for Pat and, finally, for Jill. Stanley has started to sob, but I give his hand a squeeze and encourage him to keep fighting. He looks me in the eye and says: “I’ve never given up in my life – I am a Gunner!”

And what message does he have for Jill? Simply: “I love you.”

I am very worried, of course

Jill is patient and calm and taking things in on the phone. She asks for descriptions because she cannot be there herself; of Stanley, of the room, and of the staff caring for him. “I’m very worried, of course,” she says in her matter-of-fact way. I describe the situation and the machine that pushes air into his lungs, and she tells me she calls the hospital for an update every morning and every evening. Then she shares her pain.

“The hardest part is that I can’t see him,” she says. Jill has been with Stanley since forever. He suffered a compound fracture in 1956 in a motorcycle accident when he worked for the Forestry Commission, she tells me. He was responsible for planting some of the trees at Goodwood.

His fracture could not heal and he lost his lower leg, and so the relationship with Blesma began. Stanley retrained and worked until the age of 58, “which was amazing,” Jill says, with a hint of pride in her husband’s achievements. She pauses. A life, and a lifetime, are hanging in the balance. We return to the trees.

“Stanley told me about the trees, Jill. If he doesn’t make it – I mean, if he dies that is,” and my eyes are full of tears now, “he would like his ashes to be scattered amongst those trees.” The next pause seems to last an eternity.

“I didn’t know that,” she replies. “Do you have a message for Stanley?” I ask her.

“Tell him he’s my one,” she says quietly. “He’s my one."

Stanley has been moved. From the EAU he has gone to Clandon Ward and a new clinical team is looking after him. Clandon Ward, like all of Levels C and D, is looking after coronavirus patients. The wards are full. For patients like Stanley, full PPE is needed at all times. All the patients are closely monitored 24/7, tended, turned and cared for.

At the age of 85, the statistical likelihood of Stanley being able to beat this virus is low. Everybody knows it. This amazing team has come together from all areas of the Royal Surrey family; from research medicine, gastroenterology, outpatients nursing and the central ward – staff who are all expert in aerosol-generating procedures and treatments.

The grief and trauma rippling through these coronavirus wards are palpable, and the way the staff have bonded to support, encourage and motivate each other is the most incredible thing. One member of the team comes up to me and whispers: “Please, not Stanley. Not another one.”

There's hope for Stanley

Stanley would like a blessing. He doesn’t need to know about the statistics because he knows for himself that time, opportunity, and chance are all tight. He has another message for Jill. He is struggling to breathe, but today he asks for the mask to be taken off. He would like a cup of tea, too. Dr Beth in the clinical team is the medical lead, and allows for 15 minutes.

Stanley is refreshed by the tea and feels half-human again now he is free from the C-Pap. His skin is sore from the rubbing. I ask if he is feeling any better, and he smiles the biggest smile as colour rushes into his cheeks. We seize the moment, whip out a phone to add to the decontamination procedures later, and take a selfie, giving a thumbs up for Jill. And in that photo is all of love and all of healing, and there’s hope for Stanley yet.

A letter to Jill to accompany the photo…

Dear Jill,

This situation is turning many things on their head; many old certainties and ways of doing, and of being, and of loving. I think I can be sure of this, however; Stanley does not need me as a go-between in order to know that your love for him is complete and constant and unending. He has no doubt about it. I think the pleasure he receives from me in his situation is knowing that I know about your loving relationship at a deep level, and that my

ears have heard the “I love you” and that I am able to repeat it.

Stanley was asking if you had the photo yet. “She’ll love it!” he exclaimed. I said that I was on my way to deliver it to you today. “Tell her I love her!” he said to me first. “What are you waiting for?” he said to me next.

You and Stanley are in my prayers, and this comes with my love.

Jill is adamant: “He’s not to know. He mustn’t know.” She is not well and the GP suspects coronavirus.

She buries her fears for his recovery. She places the picture of Stanley inside their house, and stands boldly for a socially distanced selfie to send back to the ward. I stand two metres from the door shouting messages of love at her, and wonder what the neighbours must be thinking.

“Tell him I will have his jacket ready for him to come home in.”

Stanley is over-the-moon happy. Would he be if he knew that she was ill, too? We do not know where the illness will go with her. Silence governs this moment between us all. In his hands is the photo of Jill from yesterday, freshly printed in the office, the first time he has seen his wife’s face in two weeks of illness.

Some tears have fallen on the paper, causing the ink to run. “Don’t worry about that, there’s plenty more copies to come,” I tell him. The Clandon staff on duty have seen it, the staff in EAU will see it later, and we all root for Stanley and Jill. He hasn’t given up, and knowing his Regimental blazer will be waiting for him gives him another boost.

“Once a Gunner, always a Gunner!” he tells me, reciting his old Army number again. We have prayers and a blessing again, and we end with Jill. Always with Jill. Stanley is getting better. He has turned the corner and is improving every day. It is slow, but it is real. This man, who has wrapped us all in his love for Jill, will be going home after a period of rehabilitation in the community hospital.

Jill has recovered too, and is waiting for him with afternoon tea and cake at the ready.

Going home in the morning

Joining the staff for a clap for Milford Hospital one Thursday night, I hear that Stanley is going home in the morning. Dr Helen, the consultant, tells me he has been waltzing on the wards – literally!

Everyone has come to Milford to stand on the grass in the evening sun and clap. The chief nurse stands shoulder-to-shoulder with the most junior doctor, the community matron with the healthcare associate. Those who have worked a full day stand exhausted with those about to work a full night. They are clapping the patients, they are clapping each other’s endurance and forbearance, acknowledging each other’s sadness at the ones who have been lost, and driving on each other’s hope. Gratitude ripples across the lawn.

The walkie-talkie takes the sound inside to the wards, and to the staff and patients there. Many neighbours have wandered over to show their support. The children are waving and clapping from the balconies of the flats, and display their NHS rainbows with delight. Eventually, the sound gently fades, but the pride in determined strength remains and glows in the hearts of those present. Final conversations, greetings and goodbyes are made, and, revived now for whatever tomorrow holds, people melt into the night.

“I’m not good with words,” Stanley says, “so I want you to give a message to the Board for me.” It is night-time and everyone else on the bay is asleep. “The way they have looked out for me and cared for me and my wife since I’ve lived in this part of the world, and here I am again. Thank you for saving my life.”

Stanley would like a prayer and blessing before we go our separate ways. We pray for the EAU, and for Clandon, and now for Milford and, last of all, for Jill.

“You can’t see it, but I’m travelling to Jill now!”

Adrian Teare, Padre 106(Y) Royal Artillery is the Lead Chaplain at the Royal Surrey NHS Foundation Trust

We can help

We are dedicated to assisting serving and ex-Service men and women who have suffered life-changing limb loss or the use of a limb, an eye or sight. We support these men and women in their communities throughout the UK. Click the link below to find out the different kinds of support we offer.

Get Support

Leave a comment

Join fellow Members and supporters to exchange information, advice and tips. Before commenting please read our terms of use for commenting on articles.