A beacon of hope for amputees everywhere

A decade ago, a PhD student from Imperial College London, who was also in the Army, noticed the types of injuries that troops were sustaining from landmines detonated under vehicles in Afghanistan.

He believed some of these injuries could be prevented, or the outcomes improved, and studies got underway. The project was initially called Imperial Blast and was a collaboration between the Ministry of Defence and Imperial College London.

In 2011, it morphed into the Centre for Blast Injury Studies (CBIS). Since then, the Centre has become a bustling hub of research into numerous topics by staff with backgrounds as diverse as engineering, physics, life sciences, medicine and computing.

Today, research is being carried out on the medical conditions most associated with injuries caused by IEDs; investigations are on-going into protective clothing, socket improvement and Direct Skeletal Fixation; and there are collaborations between military medical officers, civilian engineers and scientists.

This mix ensures the research is solely focused on improving outcomes for Service personnel and veterans. The Centre’s research projects, led by staff at the top of their fields, are often directly relevant to the future wellbeing of Blesma Members and, as the problems faced by injured veterans have changed over the years, so too has the focus of the Centre.

“The Royal British Legion initially put £5 million into the CBIS and, a few years ago, added another £5 million to take our work through to 2021,” explains Alison McGregor, Associate Director of the Centre.

“Imperial College has also contributed £3 million in-kind in terms of staff and facilities, and we have been especially fortunate to have had a number of military medical staff, who have been funded by the Ministry of Defence, embedded within the Centre over the years.”

As active conflict has wound down, CBIS has conducted more research into what happens next: how to mitigate for future injuries, for example; design better protection for soldiers; or look after a young generation of injured veterans and keep them healthy as they age.

Alison was brought in to look at this last area, and takes the lead on all things related to rehabilitation and long-term health.

“We studied Headley Court (the Defence Military Rehabilitation Centre has since moved to Stanford Hall in Leicestershire) to see how it was thriving and how we might be able to maintain what it had achieved,” says Alison. “Our team at CBIS is multi-disciplinary, with faculties such as engineering, computing and natural sciences all involved. We are gathering lots of different expertise under one umbrella, and we collaborate closely with colleagues in America, with surgeons in Beirut… with people all over the world.”

Research

CBIS is based in London, but as its research requires a great deal of crossover – imagine a medic advising an engineer on stump problems as they try to design a better socket – people with diverse disciplines are pulling together to find unique solutions. It also means close connections with associations like Blesma.

“I also feel protective towards them. I can see their potential future health issues, and I feel society hasn’t been proactive enough about the issues they may face. Ours has become a partnership, and we are hoping to address some of the questions they have started to ask.

We’ve got some work coming out soon about bone changes, for example, that will be important for many Blesma Members. We’ve been looking at conditions such as arthritis – how we manage, understand, and prevent it. We’ve found that amputees often experience changes in bone quality in their thirties, and start to suffer from issues like osteopenia and osteoporosis."

“I find working with veterans – looking at how they have faced injury and gone on to live their lives and achieve so much – to be hugely inspiring"

Alison McGregor

“We’ve discovered that bone changes in amputees are often the result of a loading phenomenon because bones aren’t loading in a normal way. That means that it’s not a systemic or hormonal issue, so we can work on the design of sockets to help alleviate the problem. It also means that this condition needs to be treated mechanically and not with drugs, as they wouldn’t help."

“If we redesign sockets, we can maybe simulate some of the loading and muscle pull that are needed to avoid osteoporosis. We’ve done it theoretically, but further research will corroborate that. Hopefully, the end result can be smarter sockets that don’t rub or hurt as much, and which look after bone health as well.”

Blesma has been consulting directly with the CBIS to help identify the most pressing problems faced by those who have undergone amputation. “One of the reasons we set up the Military Amputee Research Advisory Group was because we wanted amputees to bring us their problems rather than us to try and decide what their issues might be,” says Alison.

“Blesma has been brilliant for that. For Members to come in and be subjects for our studies, we needed the buy-in of Blesma, Headley Court/Stanford Hall, and military representatives. They have all helped so much."

“The Association has participated in surveys and studies, and shared with us the issues its Members are experiencing. Blesma has encouraged us to address long-term rehabilitation needs by putting us in touch with amputees who aren’t doing so well or who don’t feel as though they are able to make the best of things."

“The Association has pointed out that its Members aren’t just those injured on operations, they are also people with diabetes or other issues. That ensures we see the broader picture, and translate to the broader population of amputees and NHS patients.”

You wouldn’t think there is much Alison could still learn in this area: she is a former physiotherapist who studied a bioengineering masters and doctorate, and is now a Professor of Musculoskeletal Biodynamics. But, she says, she is still learning every day – and Blesma plays a big part in that.

“I used to work in elite sports medicine, and military veterans have a similar mindset to athletes,” she says.

“They’re an easy group to work with because they contribute, they’re motivated, they see the bigger picture, and are always prepared to give back. They’ll think about things from their recovery that will help others. These are all very impressive traits.”

MEET THE TEAM

With such exciting collaborations in place, whether to understand back pain, arthritis, biomechanics or any number of other topics, the CBIS is a beacon of hope for amputees everywhere. We spoke to some of their researchers to discover just a few of the recent areas of study…

Louise McMenemy

Give us some background to this procedure…

Seven or eight years ago it was noted that some amputees had used their war pensions or payouts to travel abroad – mainly to Germany or Australia – to undergo Direct Skeletal Fixation [also known as osseointegration]. Titanium rods are permanently inserted into the thigh bone, with an abutment sticking through the skin so a prosthetic limb can be attached directly to an external fitting.

Is the hope that this will be an available treatment option in the UK in the future?

A UK team was sent to work with surgeons pioneering the procedure in Australia. The UK team learned how to perform the operation, looked at costings, worked out what rehab looked like... The UK’s first patients are approaching their five-year follow-up. The study we published was in response to their two-year follow-up.

What did you want to see from the study?

Firstly, we hoped to demonstrate that the operation is safe, and secondly that it improves outcomes for the amputee. It’s important to point out that this operation is not for everyone. If you can use traditional prosthetics, you should continue to do so. But if you use a wheelchair for more than 50% of the day, it might be a solution for you. We have been cautious in our approach because this is not an experiment.

But, generally, patients are doing well?

Yes. This operation does get people back towards full fitness in an incredible way. Attached to the abutment, for example, is something called the ‘failsafe’, which will give way before the bone breaks if it is twisted. The weight limit is 110kg, and the only problem we’ve found is people trying to lift more than that in the gym! It shows how well they’re doing – living life to the full, running around the garden with their kids, all those kinds of things…

What sort of negative issues are these amputees facing?

There are on-going things to look at. The skin can get infected where the abutment comes through, for example, so sometimes there is a need for antibiotics or further operations. Our main worry is infection travelling into the bone, which would result in having to take the stem out and which, in turn, would mean not being able to go back to using regular prosthetics. It’s not a miracle cure, but the study shows that people are doing well, and hopefully it will encourage more amputees who could benefit to consider Direct Skeletal Fixation.

You’re also carrying out research into momentum offloading braces to help those with foot and ankle injuries…

Yes. We [the CBIS and military colleagues] are studying how people are getting on with what we call the Bob Brace. It works for a lot of patients with lower leg nerve injuries, but it’s not for everyone so we’ve been looking into different injury patterns and what makes the difference for some. We are now fairly confident that we can predict who the brace will work for in the long term. Rehabilitation can take up to 18 months, so hopefully this research will be helpful for people considering the brace.

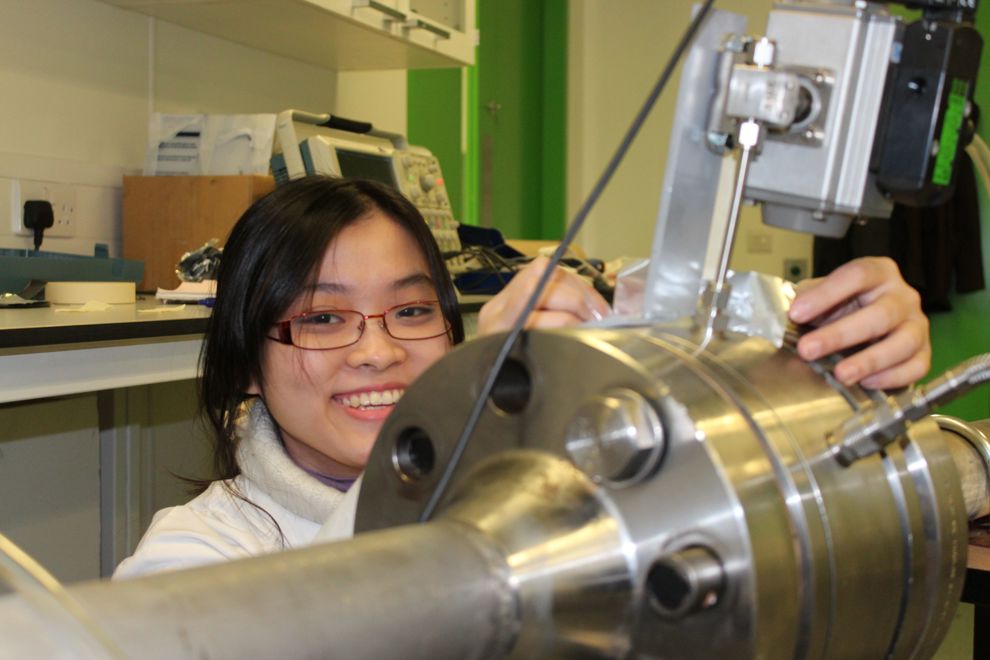

Thuy-Tien Nguyen

What motivated you to research battlefield blast injuries?

I’m interested in shock scenarios – extreme pressure, temperature, and velocity. It’s not something you see in everyday life, so it is interesting to learn about. I did my BSc and MSc in physics, but I was interested in the Centre for Blast Injury Studies because it is multi-disciplinary; you have to learn about biology, medicine, engineering… it’s a good challenge.

You’ve been examining how explosions affect the tibia…

Yes. When you’re looking to protect the tibia from explosions, you need to look at the structure of the bone – the biology, physics and mechanics – then you have to examine different protective fabrics, textiles and weaves, and how things knit together.

How do you hope your study might eventually assist military personnel?

At the moment, the people who are working on this kind of protective equipment don’t necessarily know a lot about the injury mechanism and criteria – there isn’t much information out there for them to reference. This study should help inform them.

How might it do that?

We are trying to understand the threshold for different kinds of bone fractures so that we know what to look for in protection. In the long term, we want to be able to advise the Ministry of Defence how to improve military trousers. I think the solution will be thin liners that are attached to specific areas so they aren’t too uncomfy or add too much weight. Maybe we can look to keep fragments or sand out of injuries, too.

You’ve been given some insight into this world by a Blesma Member…

Dave Henson was a PhD student here and is now a member of staff. He’s talked about his everyday requirements and challenges, and that has given us an understanding of how it is for people who have been injured. We also have open days, when people come in to talk about their experiences. It is great to have this information and hear what is important for both rehab and injury. We need to have genuine insight rather than just information on a piece of paper.

What are you working on next?

I’m researching how blast fragments penetrate the skin. Skin is a very complex structure and many injury models have to neglect its effects or assume it is the same as muscle tissue.

Shruti Turner

You were set to join the RAF…

Yes, I went to Welbeck Defence Sixth Form College but I ended up being medically discharged; I had knee problems and couldn’t run or play sport. Suddenly, at 18, my career and hobbies were taken away from me. I’m still fortunate compared to many, and it motivated me to do something that could improve people’s quality of life. A lot of biomedical engineering is about extending life, but I also think what’s the point of living longer if we’re not going to have quality of life?

You’ve completed a research project on socket fit…

When people talk about prosthetics, they don’t always discuss socket fit. There are many exciting technological advances such as brain-controlled prostheses, but the part that is really important for many amputees is the socket. It doesn’t matter how advanced a prosthesis might be, it is of no use if the socket isn’t right. It might not be quite as cutting edge, but I feel that improving this area can have so many benefits to amputees.

What did you discover?

I carried out surveys and interviews with amputees and rehabilitation clinicians, and found that many of the issues they face are related to socket fit. Many will perhaps look at the research and say: ‘Yeah, I already knew that’, but it’s important to document it because

in academia, if something isn’t documented, it’s like it’s not there. We needed to share this information so researchers, engineers and clinicians could see it and realise it is a priority. There isn’t much on record about what frustrates those going through rehabilitation.

How can these discoveries improve amputees’ lives?

It’s important to point out that prosthetists do an incredible job. Our bodies are ever-changing, and things can fluctuate, causing discomfort and pain. In this research, amputees share how their life has been impacted. Not everyone wants a robotic limb or to become a Paralympian, but they do want to go to the pub or have a day out with their children. If we can make strides to improve the socket, making them ore adjustable or adaptable to change in volume, more breathable or more lightweight, that can help.

You’re working on an app to address these issues…

Yes. A sensor network inside a socket communicates with an app via Bluetooth to create a 3D pressure map which allows you to ‘see’ what’s going on in the socket. It means clinicians can track how things change. Someone may be walking in a way that puts pressure on a certain part of the residual limb, for example, and this information can help prosthetists adapt the socket. Or someone lacking sensation in a particular area might not be able to sense a problem until a sore develops – so we could prevent that, too. Hopefully, it will help in lots of ways, although I think we will always need a human to complement the tech!

Leave a comment

Join fellow Members and supporters to exchange information, advice and tips. Before commenting please read our terms of use for commenting on articles.